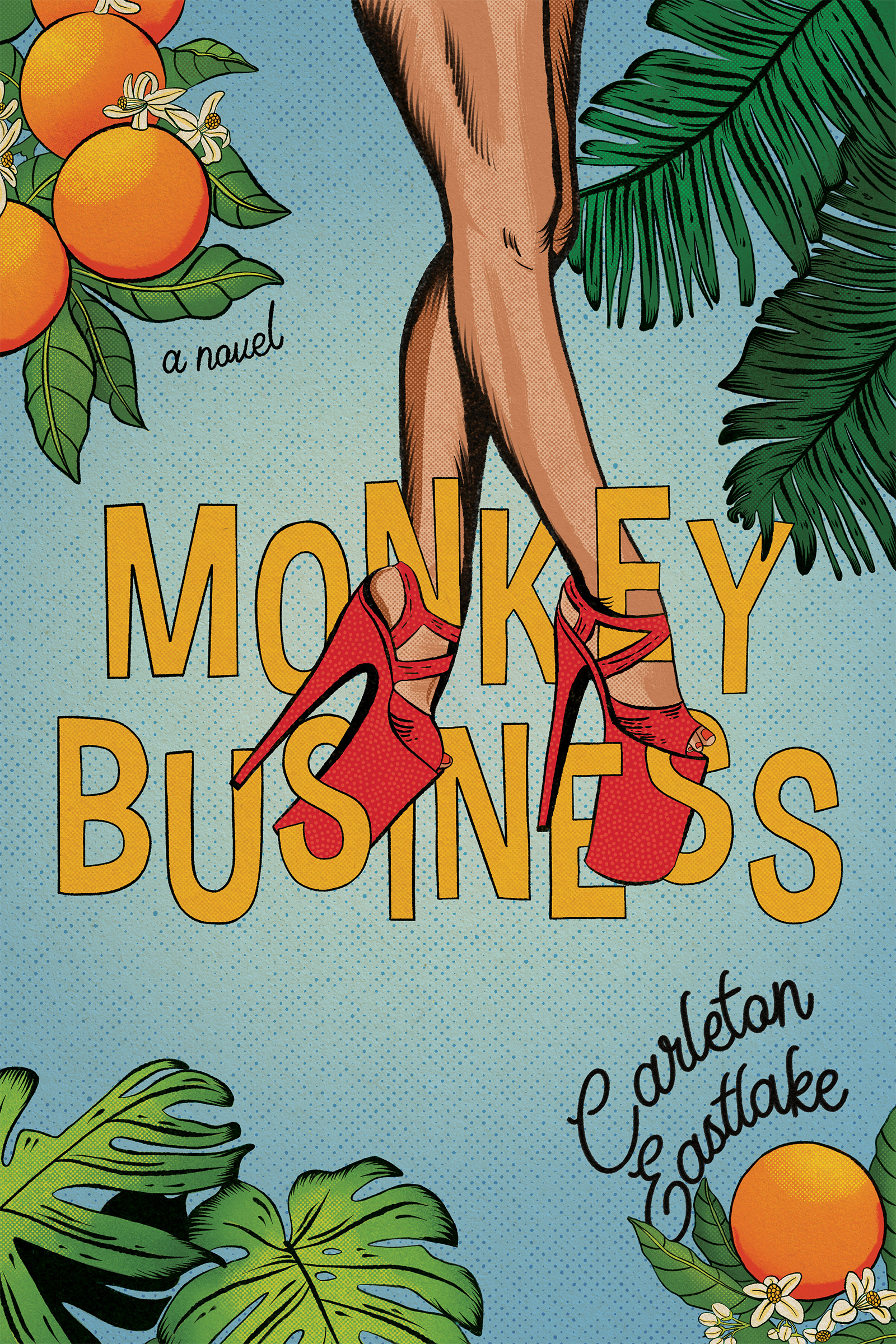

Coming Spring 2022

Carleton Eastlake

My Story...

I was born in New York City in 1947 during a famous blizzard. My mother, Marion Nelson, wrangled Arturo Toscanini for NBC Radio. My father, Alfred Chesmore Eastlake, was a medical researcher and physician at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital.

grandparents -

Once upon a time a

long, long, long time ago...

They named me Carleton Chesmore Eastlake so I’d have eight letters in each of my names.

Academic and then Public Health Service appointments for my father carried us to New York, Denver, Portland, and Paris before he left the Service to enter private practice in California. He also raced cars.

I attended thirteen schools in nine cities before graduating from high school and, since my parents’ marriages were as changeable as their residences, became acquainted with a stepfather and three stepmothers, a journey that gave me an abiding appreciation for comparative anthropology, ethology, and child psychology.

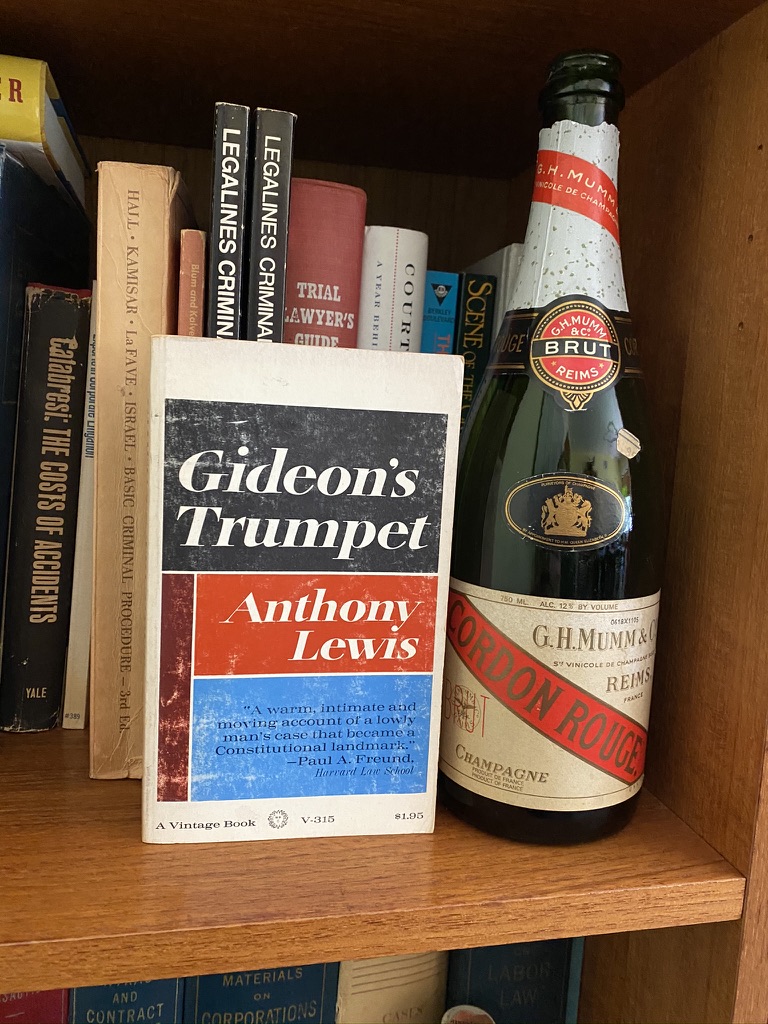

The book that inspired me to

go to law school –

and the bottle shared with my

best friend the day I got in.

After transferring from Columbia, I finished a degree in Political Science at UCLA - and ten years later took another major in Psychology. While at UCLA I began my career in imaginative writing by serving as a campaign staff writer for a California Assemblyman.

He won his election; I applied to law school. Politics played a part, but I was also inspired by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Anthony Lewis’ book Gideon's Trumpet, which celebrated the struggle for justice in the then-new era of human, criminal, and civil rights. The television series The Defenders may also have been an influence.

Still, although it sounds terrible to say, law school was my Plan B; somewhat ironically, since I later taught graduate screenwriting at UCLA, the school had discouraged my becoming a novelist by refusing me entry into the undergraduate creative writing program.

(And I might add, some hoped law school would be Plan C. The day I got my admissions letter I overheard my second stepmother on the phone telling a friend, “Of course his father is disappointed he got into Harvard,” which must be one of the more interesting lines ever voiced in true life. The reason: he hoped the law schools would turn me down and I’d finally go to medical school.)

Harvard has a very large law library.

That’s my wife at the far end.

My writing career took an interesting turn into non-fiction when I spent a law school summer at NASA editing a collection of reports on the Human Factor in Long Duration Manned Space Flight. Appalled by the heroic but illogically deadly pacts some astronauts had made to live or die as one, I contributed my own article on Survival Homicide – an analysis of the legal, ethical, psychological, and military logic of what to do if the Manned Mars Mission encountered a calamity which left the astronauts with the resources to return only a portion of the crew to Earth.

(My advice: saving as many lives as possible would be more genuinely heroic – and sensible – than romantic but futile all-or-nothing last stands against the cold mathematics of deep space, Mars being even harder to return from than the Moon.)

In 1972 I completed a J.D. degree cum laude at Harvard with a concentration in law and the social sciences, including a little graduate anthropology work and quite a few class hours in psychology as it related to criminal law and public policy – much of it taught and co-credited with the Medical School by the then-young and already-let’s-say-interesting criminal defense attorney Alan Dershowitz and the psychiatrist who literally wrote the book, Alan Stone.

An unexpected benefit of the co-credited classes: they let me point out to my father that I’d finally earned an A average in medical school.

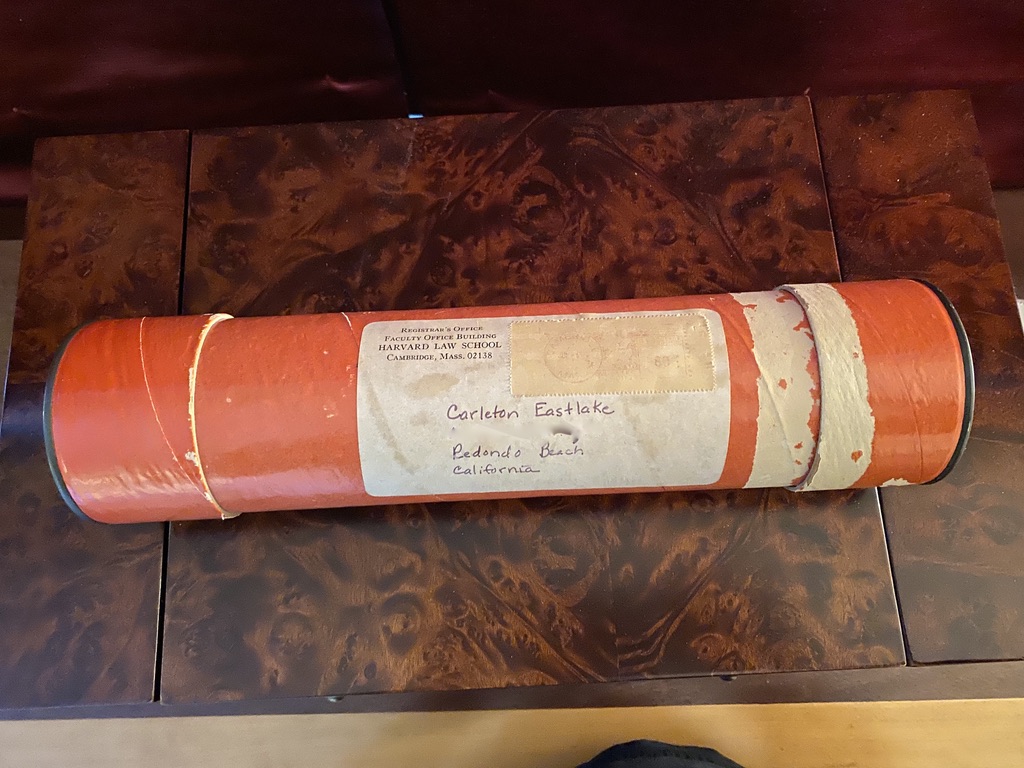

My Harvard Law School diploma.

They mail it inside this tube and it’s still there.

Seemed more interesting than framing it.

Probably not a surprise, my graduate thesis addressed the comparative anthropology of the rates of murder, suicide, and judicial execution in three purportedly non-violent cultures to test the hypothesis that no human society escapes a minimum rate of self-inflicted harm. (The answer: none do. But some early, optimistic anthropologists were terrible at statistical analysis.)

You may have detected a theme here: I was searching for ways in which unhappy families, unhappy voters, and unhappy astronauts could be persuaded to discover better answers for themselves.

My law school days, however, were not at all mirthless, nor my aspirations to be a writer forgotten: I also ran the largest nightclub operation in Boston and composed humor pieces and cartoons for the student newsletter. Although I’ve wisely never published my poetry, I did read it to my girlfriend on the shores of Lake Waban.

After graduation, I joined the Federal Trade Commission. Just reformed by Nader’s Raiders, the FTC was taking an aggressive lead in promoting consumer health and safety while attempting to persuade corporations and consumers to behave on the basis of science and common sense rather than advertising-excited emotion, fraudulent practices, and greed.

The flag is hanging over

my office window.

In a very few years I, and several hundred other people, managed to put those nutritional labels on the sides of cereal boxes, mandate uniform fuel economy ratings for new cars, create the first fair credit reporting laws, and quite a lot more.

The FTC also made me, briefly, the anti-smoking nicotine-testing tobacco czar of the United States, which put me in command of scientists in white coats hidden in the attic of our headquarters building where they operated a gigantic smoking machine later banned by the EPA on the grounds that it, in itself, was seriously polluting the environment.

The program certainly worked for me: I gave up smoking.

In 1974, I was appointed Confidential Attorney-Adviser to a Commissioner who was what I still think of as a true, if extinct, Republican: he was dedicated to promoting free markets in which no one had concentrated power and everyone had perfect knowledge. Following his departure from the Commission, I spent a year in private practice as a white-collar crime and complex case litigator before returning to the FTC where I served as Acting Director of the Los Angeles Regional Office.

During my time, we collected a billion in today’s dollars in consumer relief – which made us a target of the newly elected Reagan Administration.

My testimony, immortalized.

As you can tell from the cover design,

Congress hopes no one

will ever read it.

I resigned from the FTC to testify before the House Government Oversight Committee that the Reagan Administration was undermining the consumer protection and antitrust laws of the United States, a performance that won me a footnote with my name misspelled in Naomi Klein’s otherwise excellent book No Logo, but which in no way checked the further decline of American industrial democracy.

I’d begun writing screenplays and half-finished novels while at the FTC. In 1984 I broke into Hollywood by getting myself hired to write an episode of V, a science fiction series which – I am not making this up – featured evil aliens whose strategy to conquer the world included discrediting human scientists as spreading fake news while the aliens established neo-fascist youth groups.

Can science fiction foretell the future? Yes.

I explained to my fiancée that I intended to work in television only long enough to save up the money to finish a novel. Her friends suggested she reconsider the engagement; instead, she married me and having written the famous episode of Dallas where America discovered who shot J.R., herself published a series of novels.

Becoming co-executive producer of Steven Spielberg’s series seaQuest DSV somewhat lucratively confirmed me as a science fiction writer-producer, so I stayed longer in Hollywood than originally planned and worked, mostly as a senior writer-producer or showrunner, on twelve series, ranging from The Equalizer to The Outer Limits.

My father’s favorite, of course, was The Burning Zone – it was about a team of doctors. (Who, come to think of it, were fighting new pandemics for the CDC. Who expected the COVID virus? Just about every science fiction and TV writer in the world. And our science and medical advisors.)

.jpg)

My Hollywood work often reflected the issues I’d addressed as a lawyer. On The Equalizer I dramatized the horrors of the military dictatorship in Chile and campaigned against the dismissive attitudes of the police towards stalkers; in a 1998 episode of The Outer Limits I explored how America might respond to the sort of mass terror attacks that in the real world came in 2001.

Some of my Hollywood work continues; I currently have the Elizabethan adventure comedy Cloak and Dagger under development with eMotion Entertainment.

I’ve also on occasion served as a media consultant and futurist for various government projects related to national defense, including work concerned with dissuading at-risk youth from engaging in violent extremism. I've done some of that work in affiliation with the University of Southern California's Institute for Creative Technologies.

In 2020 I sold my first novel, MONKEY BUSINESS, to Red Hen Press for publication in Spring 2022. It’s the story of a conflicted TV writer on location at a Florida studio who becomes obsessed with a mysterious woman at a nightclub when she upends everything he thought he understood about life, limerence, bonded love, power, creativity, paintball combat, and what psychologists and philosophers refer to as the Hard Problem of human consciousness. Monkeys – and parrots – do play a role. As does Chairman Mao. And, in a cameo appearance, NASA. It is in no way autobiographical.

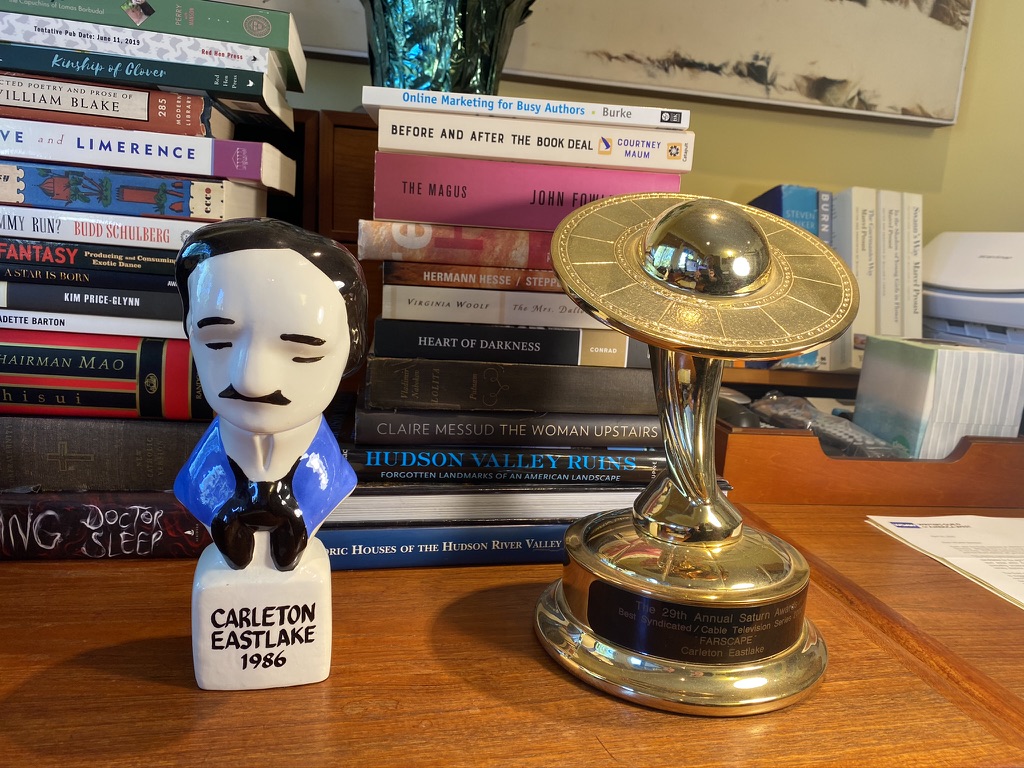

I’ve shared in an Edgar Award for best television episode (The Equalizer) and a Saturn Award for best science fiction cable series (Farscape) and am a member of the Writers Guild of America West, the Writers Guild of Canada, the Authors Guild, PEN America, the Mystery Writers of America, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, the American Bar Association, and the California Bar Association among others.

After serving four consecutive terms on the Writers Guild Board of Directors, I now sit on the Guild’s Membership and Finance, Strike Fund, and Credits Committees. I’m also a past President of PEN Center USA and a current member of PEN International's Writers Circle.

My wife and her trees

My wife Loraine Despres, aside from being a recovering screenwriter and best-selling novelist, is a tree farmer. We live in California. My stepson David Mulholland is a military economics journalist and stand-up comedian in the United Kingdom.

Since Wikipedia articles seem to be fascinated with the topic – and influences matter – I’ll confess my religious affiliations have reflected my parents’ changeable marrages. I was born Episcopalian and Lutheran; my mother rebaptized me Catholic at age 9. After serving as Captain of my catechism team, I became agnostic. My marriage was performed by a rabbi whom I later asked to officiate at my father’s funeral to the astonishment of his friends but amusement of my final stepmother. I hope there’s a Higher Power but doubt that in any sense It is fashioned in humankind’s image.

I am also influenced by Freud and his psychological descendants, who although possibly wrong in most details will likely be found more right than we wish to know. Studying the ethology of other great apes and monkeys tends to confirm – and illustrate – that view.